Broken Ground

composed 1995

duration 37 minutes

Composer’s Essay for DM Symphony program book, May 11&12, 1996

Broken Ground was commissioned by the Des Moines Symphony Orchestra, the Iowa Sesquicentennial Commission, and Grinnell College in honor of the sesquicentennials in 1996 of the State of Iowa and Grinnell College. Its creation brought together 6 poets, a composer, and a large network of performers and supporters in pursuit of a common goal: to reflect on the relationships between the people and landscape of the prairie Midwest through the arts of music and poetry. In creating the work, we sought to express the beauty and harshness of the prairie as well as the intensity of the human response to its rigors and fruitfulness.

All six collaborating poets write with a distinctive lyricism about the midwestern landscape. They include poet-farmer Michael Carey from southwest Iowa, Native American poet and novelist Ray Young Bear from the Mesquakie Settlement of the Fox-Sauk Tribe, poet and essayist Mary Swander from Iowa State University whose work often focuses on the Amish culture around Kalona, poet and novelist Paula Smith of the Grinnell College faculty, songwriter and humorist Dan Hunter of Des Moines, and National Book Award-winning poet Ed Hirsch, a Grinnell College graduate from the University of Houston. In creating this work for the Iowa and Grinnell College Sesquicentennials, the poets and I sought to find literary metaphors and musical styles that transcend the boundaries of our region while remaining firmly rooted in the rolling landscape of the prairies.

Work on Broken Ground began in the summer of 1994, after favorable responses to the idea from the Des Moines Symphony, the Iowa Sesquicentennial Commission, and Grinnell College. In an early meeting, we settled on the theme of the four elements — earth, air, fire, and water — as a unifying focus for the different poetic voices. As one of the poets said, “That’s what all our poems are about anyway!”

Over the ensuing months, the poets sent me dozens of texts to read through, and I began to circulate those that I found most suggestive musically. Several of the poets chose to work explicitly off of each others’ words, resulting in an unusual degree of cohesiveness among the imagery used by the different writers. Michael Carey’s “Once when the ground was holy,” for instance, becomes “The ground was holy but the wind was harsh” in Edward Hirsch’s retelling. Hirsch’s “the wind was harsh” transforms into Dan Hunter’s “Only the wind.” Hunter’s “graveyard’s broken ground” becomes Mary Swander’s “When the ground was broken.” And Carey’s resurrecting blades of grass become Swander’s “blades of grass turning brown, turning green.” Listening to these different poetic voices conversing with one another was one of the great delights of working with these marvelous words.

As I began contemplating the music, my first task was to arrange the poems into a coherent and musically promising succession. In doing so, I tried to listen both to the sense of the words and to their sound. Ray Young Bear’s watery snow and ice (movement 1) suggest a primeval landscape from which all else emerges. Michael Carey’s “Once When the Ground Was Holy” (movement 2) depicts a holy and magical ground. It and the next poem — Paul Smith’s “Rhizomes” (outer sections of movement 3) — provide the base from which arises the variegated life of Edward Hirsch’s “Iowa Flora” (middle section of movement 3.) Smith’s poem provides the “cradling web” for Hirsch’s flora, just as it frames it musically at the start and end of movement 3. “Ocean of grass” (movement 4) ascends above the ground and into the air for a poignant picture of wind, fire, loneliness, and loss. Dan Hunter’s “Only the Wind” (movement 5, beginning) portrays a triumphant wind sweeping eternally over gravestones. And Mary Swander’s synoptic “When the Ground Was Broken” (movement 5, conclusion) steps back through earth, air, water, and fire, ending with a hopeful image of “blades of grass… turning green.” One hears, in this last line, a response to the Midwest’s great flood of 1993, depicted resoundingly in the poem’s third stanza: “every cloud darkened and the rain came rushing down, the ground broken away in chunks, floating downstream.”

Faced with such potent words, what is a composer to do? Listen, ponder, and let the words take command. I often found myself notating and renotating rhythms irrespective of pitches until I felt that the cadence of the words was just right. I listened for suggestive phrases to establish the musical style of each movement. The undulating lake and cool quiet springs of Young Bear’s ice-glazed landscape suggested a certain kind of music; the galloping horses of Carey’s holy ground suggested another; and the driving underground energy of Smith’s rhizomes still a third. I engaged in evident word-painting. When “the shooting stars fall down and down again” in Swander’s text, the musical lines do the same. When the insistent wind blows over the stones in Hunter’s poem, you hear its swooping lines and capricious rhythms. When the chorus sings of an “underground constellation” in Swander’s text, the pitches follow the contour of the Big Dipper, first upside-down and then right-side-up.

Movement 1, “The Ice-Glazed Landscape,” emerges from the icy cold sound of the crotale (small tuned cymbal). The texture thickens gradually and hopefully as the chorus intones the phrase “We lived here once inside and along these ancient hills.” But after this brief moment of warmth, the music settles back into the icy coolness of its opening.

After this introductory movement, movement 2 (“Once When the Ground Was Holy”) settles in to a steadier, more energetic motion. The meter is compound — beats subdividing into groups of three notes rather than two — inspired by the playful galloping of the horses described in Carey’s text, the jig-like rhythm that I imagine for the dancing blades of grass at the end, and the holiness of the similarly metered closing section of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion which I heard in concert as I was working on this piece. The interweaving oboe melodies of this movement also reflect Bach’s influence. Carey’s line “butcher, baker, beggar man, thief” reappears in Swander’s concluding poem as “butcher, baker, beggarwoman, thief,” and the two lines share the same music.

Movement 3, “Rhizomes and Flora,” weaves together two poems depicting the scenes below and above the prairie soil surface. Smith’s “silent force… working underground” is depicted through driving rhythms set up by the low brass. Hirsch’s contrasts between native and alien flora are reflected in harmonies that alternate between natural, stable chords and slightly twisted, more tension-filled ones. The first violins play a prominent role throughout this middle section. Hirsch’s poem is dedicated to Iowan Amy Clampitt, a MacArthur “Genius” Award recipient and keen observer of nature who died in 1994. The closing line concerning “the shining, cup-flowered grass of Parnassus” leads smoothly back to Smith’s poem with its “waving sea of grasses.”

Movement 4, “Ocean of Grass,” is a poignant and somber meditation on incidents taken from the diaries of prairie frontierswomen and assembled by Hirsch into a poetic structure of great incisiveness. Its villanelle form (19 lines with the first and third lines of the opening stanza appearing alternately as the concluding lines of succeeding stanzas and coming together at the end) gives rise to a musical counterpart. Line 1 is set to a hymn-like depiction of holiness and harshness, while line three is distinguished by an opening point of imitation characterized by the interval of a rising 4th. The hymn-like music, especially, grows gradually richer and more elaborate with each of its recurrences. The movement closes with a dirge-like, slow march accompanying the lines “Think of her sometimes when you pace the earth, our mother, where she was laid to rest.”

Movement 5, “When the Ground Was Broken,” begins with Dan Hunter’s “Only the Wind” in energetic, shifting meters driven by a prominent xylophone line. After a quieter, more legato section for the line “Now the stones lie silent and smooth…,” the opening, rhythmic music returns briefly, leading directly to the setting of Mary Swander’s “When the Ground Was Broken.” This closing music is a tour de force for the chorus, involving several fugal sections, echoes of earlier musical and poetic ideas, and an impelling drive towards its energetic conclusion.

The May 1996 Des Moines Symphony performances of Broken Ground marked the complete work’s premiere. Excerpts were performed previously with violin and piano accompaniment, notably at Carnegie Hall in March 1996. The Des Moines performances were supported, in part, by funds from the Iowa Arts Council.

Be Here Now

composed 2024

duration 16 minutes

This work for ten players fits in a chamber music genre variously known as a dectet, decet, or tentet. Ensembles of this size vary widely in instrumentation. Some of the best-known employ standard wind quintet and string quartet plus double bass, resembling a mini-orchestra. Be Here Now follows this model and, like an orchestra, requires a conductor.

Inspired by sonic imagery found, surprisingly, in a hiking guidebook, the music begins with small groups of hikers setting out at slow but steady and then double-time paces. Soon, instrument groups associate with components of the natural environment: wind instruments with rocks, for instance, and strings with trees. The music responds to guidebook author Edward Henry’s evocations of bellowing boulders, bold staccato rocks, muted forests, lifting melodies, spreading counter-melodies, and harmonizing ridges along the path to a rock promontory in New York’s Shawangunk Mountains known as Gertrude’s Nose. “The crescendos of rock continue to grow, and the forest interludes fade into the background as the land builds to a climax,” culminating in what Henry calls the “final stanza” from the “natural orchestra” (Gunks Trails, 2003).

As for the title of Be Here Now, it comes from a hand-painted sign of mysterious origin greeting hikers near the start of a path to a wilderness area near Santa Fé, New Mexico. Its advice to “be here now” is as germane to music listeners as to hikers. Forego the distractions of modern life and be fully present in this place and this moment. Happy hiking!

Movement I, “Row Crops and Livestock”, grew out of a conversation with the farm families of Irvy and Jeanneen Badger & Norma and Maurice Field, in rural Moorland, IA. They spoke realistically and soberly about the changes that have buffeted the farm economy, but they balanced that with an

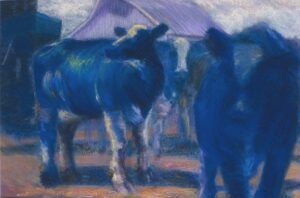

Movement I, “Row Crops and Livestock”, grew out of a conversation with the farm families of Irvy and Jeanneen Badger & Norma and Maurice Field, in rural Moorland, IA. They spoke realistically and soberly about the changes that have buffeted the farm economy, but they balanced that with an  infectious good humor and an obvious love for what they do. Like their lives, the music of this movement is alternately heroic, lyrical, and filled with irony and surprise.

infectious good humor and an obvious love for what they do. Like their lives, the music of this movement is alternately heroic, lyrical, and filled with irony and surprise. spoke about the rhythms and joys of her family’s dairy operation near Callender, IA. Between the three-hour morning and evening milking sessions, Sonja finds time to practice her profession as a visual artist. The three-part form of the music mirrors the rhythms of Sonja’s life, marked off in five-measure

spoke about the rhythms and joys of her family’s dairy operation near Callender, IA. Between the three-hour morning and evening milking sessions, Sonja finds time to practice her profession as a visual artist. The three-part form of the music mirrors the rhythms of Sonja’s life, marked off in five-measure groupings in 12/8 time corresponding to the hours of her work day. Percussive evocations of the milking equipment pervade the outer sections, leading to a mechanistic march. In the middle, though, there is time for art, in the form of a lyrical interlude.

groupings in 12/8 time corresponding to the hours of her work day. Percussive evocations of the milking equipment pervade the outer sections, leading to a mechanistic march. In the middle, though, there is time for art, in the form of a lyrical interlude.  was inspired by the sights and sounds of the wild prairie remnants still to be found in the Iowa countryside and the balm they can provide for harried, modern lives. Many of its musical ideas were notated from insect and bird sounds recorded at Kalsow Prairie near Fort Dodge and drastically slowed down with the aid of a computer. The effect is of a vibrant, magical, comforting landscape akin to that imagined by John Peterson in his poem “Becoming Prairie in Dickinson County” [Voices on the Landscape (Parkersburg, IA: Loess Hills Books, 1996, p. 108]:

was inspired by the sights and sounds of the wild prairie remnants still to be found in the Iowa countryside and the balm they can provide for harried, modern lives. Many of its musical ideas were notated from insect and bird sounds recorded at Kalsow Prairie near Fort Dodge and drastically slowed down with the aid of a computer. The effect is of a vibrant, magical, comforting landscape akin to that imagined by John Peterson in his poem “Becoming Prairie in Dickinson County” [Voices on the Landscape (Parkersburg, IA: Loess Hills Books, 1996, p. 108]: